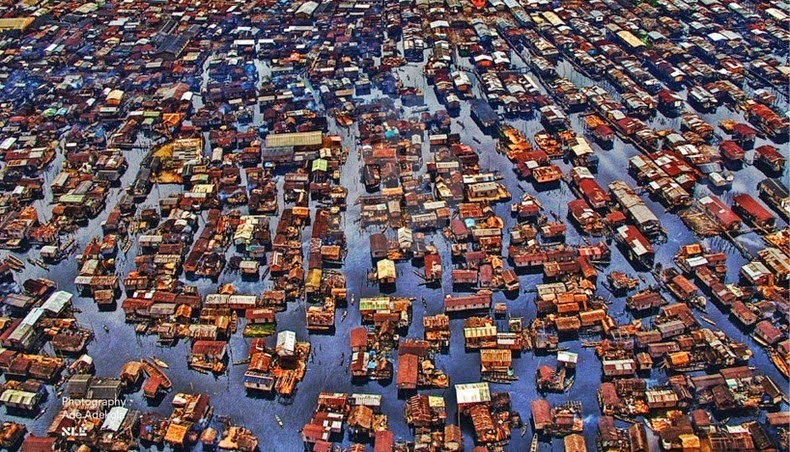

The shanty town of Makoko is located on a lagoon on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, a stone’s throw from the modern buildings that make up Lagos, the biggest town in Nigeria and the main commercial and industrial center. In this sprawling slum on the waterfront, adjacent to the 10 km long Third Mainland Bridge, tens of thousands of people live in rickety wood houses raised on slits. There are no official census records, but estimates suggest some 150,000 to 250,000 people live here.

Makoko used to be a small fishing village built by fishermen who came from Benin to make money more than a hundred years ago, before it grew into an illegally constructed one-square-kilometer urban settlement. The population now consists mainly of migrant workers from West African countries, trying to make a living in Nigeria. The oily black water is no longer suitable for fishing; it emits a pungent smell, and a thick layer of white scum gathers around the shack stilts.

The houses on water are built from hardwood, supported by wood stilts driven deep into the waterbed. Each house usually houses between six to ten people and a high percentage are rental properties. The residents use dug out canoe to navigate the canals that crisscross between the houses. Aside from transportation, canoes are also used for fishing and act as points of sale where women sell food, water and household goods.

For decades, residents in Makoko have had no access to basic infrastructure, including clean drinking water, electricity and waste disposal, and prone to severe environmental and health hazards. Communal latrines are shared by about 15 households and wastewater, excreta, kitchen waste and polythene bags go straight into the water they’ve lived on top of. The only way to get potable water is to buy them from vendors who get it from boreholes. The government provides no free water to Makoko residents. Indeed, the government doesn’t want Makoko residents living there at all. On July, 2012, the government swooped into the low-lying coastal community and demolished many of the floating houses and other illegal structures. The officials cited health and sanitation concerns, but some locals suspect that the underlying motivation is a desire to sell off the area lucratively to property developers.

The media outcry following the demolition and the community’s protest led the state government to announce a regeneration plan to provide accommodation for 250,000 people and employment opportunities for a further 150,000. Recently, a team of architects devised a floating school built from plastic barrels that has space for classrooms as well as play area.

The floating school. Photo credit: NLÉ architects

Photo credit: NLÉ architects

No comments:

Post a Comment